On Romanticism, the Fragment, and Writing in Relation

Dear reader,

Last year, I suggested that my substack could be read as a kind of ‘commonplace notebook,’ a collection of fragmentary thoughts on philosophy, ecology, the imagination, and planetary futures. In that spirit, I thought I would begin 2025 with a small gathering of thoughts, some life updates, and some excerpts from my PhD readings. Fragments, like letters, somehow feel more personal. Or, at the very least, I feel compelled to personalize them. It doesn’t feel quite right to speak into the virtual ether. Someone has to be on the other end of these things—so I will imagine that they are letters, addressed to you, whoever you might happen to be. As both a writer and a publisher, I am keenly aware that any writing is, in a sense, a bridge between past and present. Reading can be a window, a time machine, or perhaps even a seance. It involves a kind of communion with other minds (and hearts) across time and space—like Ursula K. LeGuin’s ‘ansible.’ When we keep this all in mind, writing begins to feel less and less like a solitary act. Know that you have a reader, if not an audience, and watch your voice improve. It’s the animist lesson that there is always a thou. Writing, no matter when, or where, is writing in relation.

On the Philosophical Fragment

“The imagination is unpretentious. It is a Proteus that numbly assumes different forms. Its self is to slip into another.”

- Luke Fisher, Philosophical Fragments as the Poetry of Thinking: Romanticism and the Living Present

Lately, I have been reading the German Romantics. Over the course of this past year, F.W.J. Schelling has quickly become one of my favorite Western philosophers (incidentally we share the same birthday: tomorrow, January 27). Hegel had derided Schelling as the “proteus” of philosophy, always reworking his concepts, but I have found this to be evidence of his strength. Schelling had the capacity to hold his system-building lightly—a dynamism of thought needed to match the dynamism of a living world.

I imagine Gebser nodding with approval—he spoke highly of Schelling, Holderlin, Novalis, and generally considered the German Romantics were to be early harbingers of the integral mutation. It feels like an obvious progression, perhaps, to take Gebser’s claim seriously and come to a better understanding as to why he saw them that way. At the very least, I find my own thinking at home with much of theirs. They were advocates of the role of imagination—it was the missing faculty, the ‘active’ sense that helped the mind go beyond the island of the self and find a home in the world. Friedrich Schlegel and Novalis celebrated the literary fragment for its expansiveness—the fragment, particularly the philosophical fragment, exceeded system-building, or rather, was inhabited a good balance between discursive thought and the a-systematic. Perhaps this is what Gebser meant by “systasis,” which he saw as the proper expressive form of the new mutation. Luke Fisher, in his excellent book of fragments (and essays), distinguishes the “systematic” drive of philosophy with the “intuitive.” The philosopher must be careful that the former is a support for the latter, and not the other way around. “Systematicity has its discipline,” Fisher writes in fragment 175, “but intuitivity has its discipline too: devotion to the sources of thought, to the living nous… the writing of fragments is devoted to intuitive thinking—a sibling of contemplation or meditation.” Intuitivity, then, is a devotional practice—and to what? I would suggest that it is a devotion to the world: the “appearances,” and their dynamic, open, and living ground. “Do they [the philosophers] get mired in the elaboration of thought and forget thinking,” Fisher asks in fragment 177, “or does the former increase the dynamic receptivity to the latter?”

More and more, I have found that my own writing is at home in this romantic notion of the fragment. My manuscript, nearly completed, begins to make sense in retrospect—I had the good sense to title it ‘Fragments of an Integral Future,’ but I had struggled to truly embrace the depths of the fragment. The philosophical fragment is ecological thought. It allows us to perceive the living whole in a flash—like Goethe’s Urpflanze, it is the sort of whole, or unity, which is can only be imaginatively perceived in the world’s multiplicity.

My paper, “Romanticizing the Aperspectival World” is currently going through a few rounds of edits, but I hope to publish it here.

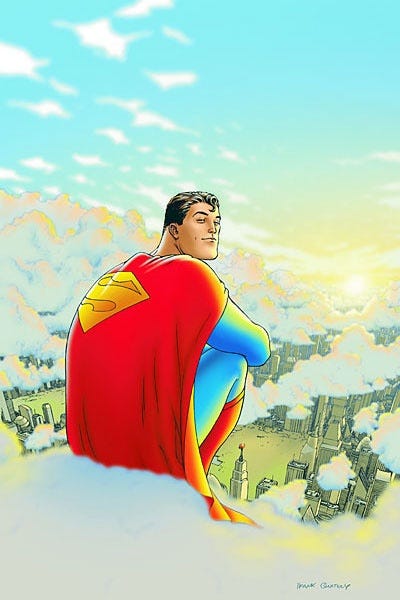

An Imaginary Syllabus (or, yet another fragment on imagination)

I have this ‘vague’ idea for a course on the history of consciousness: we begin with Pico Mirandola’s Oration on the Dignity of Man, pause briefly with F.W.J. Schelling and Johann Von Goethe before picking up Henri Bergson and Gilles Deleuze, Sri Aurobindo and Jean Gebser. Moving into the twenty-first century, we leap—in a single bound!—from philosophy to comic book literature and read Grant Morrison’s Supergods, Jeffrey Kripal’s Mutants and Mystics, before concluding with Morrison’s All-Star Superman. We find ourselves surprised to find Mirandola there, amidst the colorful spandex panels, wondering aloud about the romantic’s view of the imagination and the future of human consciousness. As an epilogue, perhaps we will revisit my own book, Fragments, to further nudge Mirandola’s image of the (super)human in a more appropriate posthuman context. As I wrote about in my book, the human, let alone the superhuman, shouldn’t be tossed away. It’s at the heart of what makes us what we are. But it needs to be thoroughly ecologized. Rendered transparent. Why, you ask? Because it’s also at the heart of what makes nature nature. Here, Gloria Anzaldua consults us on the image of the nahual, the shapeshifter, as a kind of once-and-future vision of the human being, a being of becoming that is always in radical relation. You, and the rest of us in this imaginary class, leave feeling like the “all-stars” that we are. In Gebserian fashion, we are left reveling in the newfound meaning that “the man of tomorrow” offers Mallarme’s poetic (or in Gebser’s terms, ‘eteological’) statement: “the star shapes us from tomorrow.”