Let Silence Find You

Readings for late October, early November 2023.

All Saints Day, Dia De Los Muertos

The idea for this ongoing reading series is to experiment with a kind of public commonplace book, an admixture that I hope amounts to something a bit more than a mere annotated bibliography. It’s a more personalized glimpse into my reading and writing journey—how I’m working through (or, sometimes not) unresolvable questions in an unthinkable present.

As I said, it will be personal, but it will also (attempt to) be poetic and contemplative.

When you’re working with the kind of prima materia concerning ends and beginnings of worlds and worldviews, you’re working with your own innermost stuff. You’re working with soul.

So this will be writing from soul.

Most of all, it will be an attempt to document how I am trying to live the sorts of questions that truly light up the creative fires burning in the forge.

What does a return to animism in the context of planetary futures actually mean, for example, and how do we live this new time, this new worldview, that is quickly rising up to meet us?

Perhaps it has something to do with the life I’ve started here in the green mountains of southern Vermont. The rush of life events and activities is, like ever, a kind of frenzied roar, but like the creek that ceaselessly chatters at the bottom of our hill, its movement is predicated on a greater enveloping silence. There is a deeper peace here. Things are slow enough to finally sync up with the pace of soul.

Metamorphosis can’t be hurried; becoming is as fast as our capacity to really be present to our relations, an artfulness of timeliness. Rilke wrote that “our looking ripens things,” and I think this is also true for presencing, and our capacity to be present: what’s latent is ripened insofar as we can actually become present.

I am drawn to create a space that leaves more room to share contemplative writing: work that comments on spiritual practice and creative soulwork in a “time between worlds.”

“Mutations: a public commonplace book for a time between worlds.”

Something like that. I will hold it lightly, but I would like to hold it for a while and see how it feels in writer’s hand, what Le Guin called ‘hand-mind.’

It’s not like any of this is saying something altogether different than what I’ve already started writing about here for this Substack project. I just think that the nature of the project, and what I can do here, has started to become clearer. More inspired.

Like before, I’ll be trying to balance paid and free versions of what I publish. Today, this publication will be for everyone—try it out and see if you want to join me as a paid subscriber (and, as always, my endless thanks).

Paid subscribers will also be invited to meet once a month on Zoom for Q&A, occasional philosophical-poetic workshops and themed discussions.

With this in mind here are a few fragments.

Amphibious Cyborgs

First, a note on my actual research process.

I use commonplace notebooks. I’ve used them for most of my adult life, although I didn’t really know what they were called until just a few years ago.

Everything goes in there. It’s a hybrid between a live feed and a compost bin. I let these concepts, connections, inspirations run absolutely wild and free. Most of them fizzle out, eventually, but some of them really turn into fragments of sentences or poetic insights that make their way into my essays. Sometimes I have to dig up old notebooks because, out of blue, there’s suddenly newfound connections harkening back to an old brainstorming session (…didn’t I write about those lychen or rhizomal nodes last year?). I write to discover what I think, to find my authentic voice, but the writing first looks very mulchy and messy—it’s the work of other (equally creative) parts of my mind that eventually edit and compose the mess into the appearance of an article.

Sometimes these analog scribbles transmogrify into the smooth, textureless folders of digital journaling apps (I use Obsidian these days).

In the perpetual quest to construct our extended minds, the infinite spaces of the digital tempts the researcher with a certain quantitative luster. The allure of data promises to unlock genius, emancipate the mind with mighty enhancements, cyborg augmentations.

Data can be beautiful, sure, but it’s really beauty that’s all-important in that phrase: beauty implies a certain constellation of relationships, aesthetic configurations. Knowledge has to become something more than information. Text needs to acquire the quality of texture. It needs the fuller range of human sense.

We have to roll ideas around on our tongue, feel them in the hand.

So, I have remained an amphibious cyborg, roaming between digital and analog worlds.

Commonplace books have always remained essential for my proces. More recently, Umberto Eco’s notecard method has been a revelation.

I confess, though, that the latter is nowhere near the level of organization it should be, but that seems to be its hidden blessing: my disorganized index of analog notecards has allowed for chance encounters and connections between books and ideas that wouldn’t have found each other otherwise. Perhaps I’ve fumbled my way into the “fabricated serendipity” of Niklas Luhman’s zettelkasten method.

Library angels can also and often be found in the hypertext.

Delve Deeply, or Letting Silence Find You

The etymological roots of the word “planetary,” derive from the Greek planētai, meaning “wandering (stars).” Creative soulwork—for me, at least—can be restless, like a wandering star. It needs to be amphibious, to pick things up and put them back down, only to return to them again and again with new prehensile appendages, different bodies.

Perhaps this metamorphic creativity, this restless wandering will be a characteristic of future planetary cultures.

Contemplative practice is joyfully entangled in my creative soulwork. How could it not be? So my dharma is a kind of soulmaking dharma, and I try to be forgiving when I let the meditation cushion get dusty for a few seasons (my cats will always pick up the slack for me).

As I write this, Vermont is having its first snowfall. The green hills and orange foliage have been transformed overnight into one single and uninterrupted, even joyous bright whiteness.

Snow often lands in me as a kind of childlike lightness of being, so right now I experience myself lightly, dreaming forward future months—to February of 2024—when I’ll be teaching the annual Gebser course and assigning Gebser’s ‘Winterpoem’ (Wintergidecht 1944) to my students.

Now at last the first snow falls

like a blanket upon dim powers.

Keep the fire alive now

and do not disturb the sleep

of roots and seeds.

The German editor of Gebser’s collected works, Rudolf Hämmerli, comments that “The Winter Poem… set down… in three-quarters of an hour without making a single correction, was for him [Gebser] the poetic expression of The Ever-Present Origin.”1

It is through poesis and poetic language generally that we find ourselves graced with the ability to communicate what is otherwise incommunicable. Poetic language, as Hämmerli, notes, “works through all of Gebser’s philosophical writings and is the guarantee by which the reader can concretely experience what is not to be fixed or grasped conceptually.”

So this is winter:

no longer facing the visible

revealing the invisible.

When you work on and with the kinds of materials found in the likes of Gebser (or other writers who actively connect the philosophical, poetic, and spiritual, who as Charles Taylor describes are responding to the conditions of our modern imaginary with a kind of ‘fullness,’ attempting in their work to ‘break out of a narrower frame into a broader field’)2, reading and teaching it year-to-year starts to have an affect; the material works on you.

Medium is message and massage: we unfold into new perceptual capacities, new thinking. How could it be otherwise? The stuff is potent. If you keep showing up, you will one day find yourself changed.

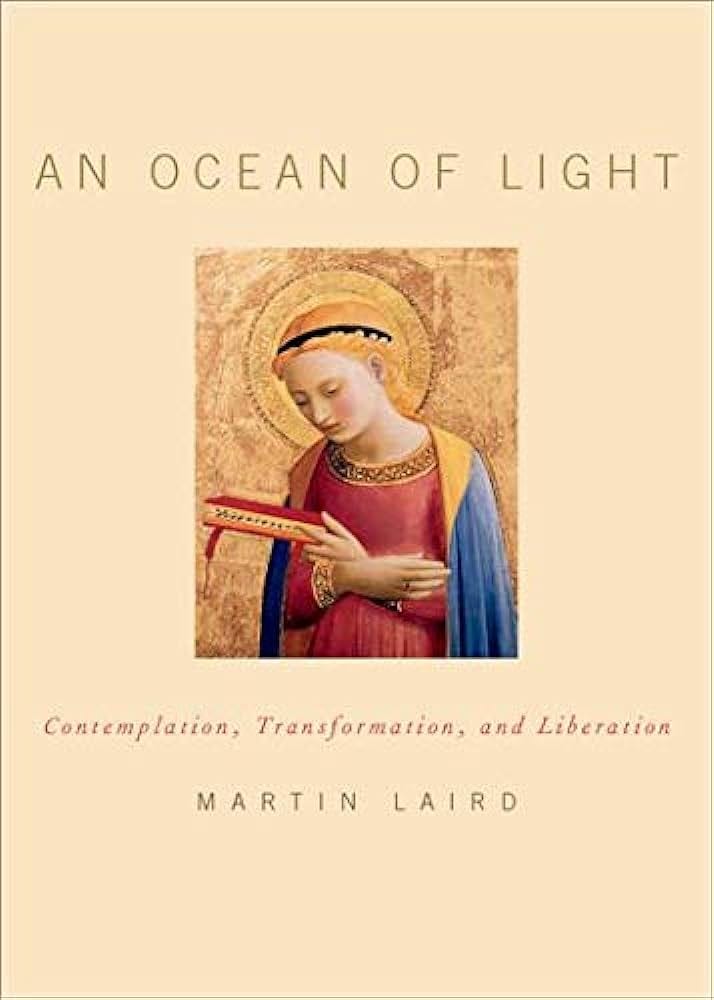

This point is beautifully illustrated in Martin Laird’s Ocean of Light, a Christian contemplative book which I flipped open the other evening in a moment of intuition, only to have an ‘aha’ moment that named a truth about my own contemplative practice.

Laird describes the emergence of a latent “receptive mind,” which coalesces in us not as not as something over and against the busy-bodied “reactive mind,” but as the innate but newfound capacity to recognize a more intrinsic “luminous ground.”

The initial return to meditative practice—for myself, at least, but I imagine many of us might feel this way—is often experienced as a kind of forced habit. That remains true until some some quiet and unsuspecting moment, like the slowness of one season overtaking another, some other capacity, a qualitatively different sense begins to take hold in us.

What takes hold is a kind of longing: a longing for and love of a full and spacious silence.

We enter silence and it enters us, like an ancient and quiet landscape.

This silence isn’t so much created or constructed by our contemplative practice as much as it becomes increasingly clarified, rendered perceptible by the gradual awakening of receptive mind.

“Our practice,” Laird writes, “which had seemed to be a mental construct to which we always returned our attention, is now not a construct at all but a vast, open space… This newly uncovered depth-dimension remains… present in reactive mind as non-clinging longing, a longing for the pulsing Truth of life we think we lack and therefore seek as for something lost.”3 Like the roaring of the creek at the bottom of the hill, reactive mind remains present as-ever, although now it is enveloped by a greater quietude.

“We know this practice: whenever we notice that our attention has been stolen we gently return our attention… with the breath… we return and return and return. Yet at some moment ripe and ready (calendar time has no say in the matter), a depth-dimension, so to speak… opens up from within our practice itself and receives us as though we were one with it.”

We begin to “delve deeply,” as the 19th century Russian monk Theophane the Recluse (and gosh, what a name!) had described. We feel that we are “being integrated into some larger mystery,” and that we are not so much seeking out silence as we are discovering how much we are this silence. “For receptive mind the distant echoes of home are not so distant as they once seemed.”

Silence arises from a place that remains intimate with the world and its appearances, with things in all their fullness. This fullness which we share with the world.

The shining winter sky

is close enough to touch;

and you too are this sky.

no reason to distinguish.

For all the stars flow through your veins.

Gebser, in his Winterpoem, states that it is the “winter’s clarity” of our own hearts that we have forgotten. “The harsh, clear air” can bring us “the brilliant premonition of possible freedom,” if only we didn’t “pass it by unknowingly.”

Distant echoes of home become close at hand:

How closely to each foot

and to each hand,

how closely to every heart

does this threshold run,

the threshold which dissolves

everything on this side

and everything beyond:

where our bonding with the outermost heavens,

opens bright, hyper wakeful

senses.

I’d like to imagine that in its admittedly more rarified and spiritual form of realization, the integral ‘mutation,’ or an integral consciousness, is remarkably similar to what Laird’s sublime writing has pointed to. I’d also like to imagine that we can trace a rough sketch of a spiritual practice: where we turn our attention towards presence, which becomes a kind of spaciousness, eventually a kind of “relational transparency” with all things, where reactive mind gives way to the blossoming of receptive mind, where past and future, “spring, summer and autumn,” and “sleep, dream, and waking” too have all become “thoroughly present,” and “interwined at all times,” yet nevertheless “completely differentiated with every breath.”

This is this “supra-wakeful realm.”

When we learn to delve deeply here, we emerge—as Gebser wrote elsewhere in The Rose Poem—“into the gentle diaphaneity of things.”4

To conclude with Laird’s poetic contemplation:5

The inner eye which beholds luminous vastness is itself luminous vastness. It is the fullness of created identity held in the fragment emptiness of an open blossom, the flower of awareness.

Aaron Cheak quoting Rudolf Hammerli in his introduction to the Winterpoem. https://rubedo.press/propaganda/2017/10/6/jean-gebsers-winter-poem

Charles Taylor. A Secular Age. 768-769.

Martin Laird, An Ocean of Light. Pages 104-106.

Jean Gebser, The Rose Poem. Composed in three sittings from December of 1945, March 1946 and December 1946.

Laird, 158.

Thank you for sharing this.

The thing that resonated with me most was how spiritual practice has to come out of some sense of longing, yet often it is difficult to connect what happens in practicing to the motivation to do it.

And then you touch this "place" of space and silence and it is the most natural thing in the world, you can't imagine losing touch with it. Until you do, and then you can't really imagine being in touch with it anymore, and the exercises to get you back there seem empty and contrived. Which in some sense they are, as it always is there. You're not trying to find it, you are learning to see it in everything.

And this longing matters. A longing for something that we have never lost, but that we cannot contact without this longing. A longing that shows us we have only arrived when we know we still have a long way to go.

Well, I do hope this is sort of what you meant to point to. Words always fail in these matters anyway, as here they have an even higher tendency than usual to mean opposite things at the same time.

Thanks for this article, makes me happy to see others poking at the edges of things I also feel I am trying to poke around.

I like the returning to things over time you mention in different states. It’s like all the metabolism in between brings the things alive to you in new ways, even the ideas themselves which have lived through you and changed you and vice versa.

I keep what I call a commonplace rhizome in an app called Craft. It is a glorious mess and serves me well!